What America Forgot, Japan Remembers (Part III): “Shikake” or The Art of Shaping Behavior Through UX Design

The Japanese seem to have a word for everything, even in a world as dry as business:

Kangaechu: “The current thinking”

Omotenashi: “Anticipating someone’s needs with sincerity and care”

Karoshi: “Death from over work”

Nemawashi: “Laying the ground work.”

Otsukaresama: “Thank you for your hard work.”

Recently, one of my favorite Japanese words is Shikake. It means: a mechanism, a set-up, a trap, a trigger.

Japanese Edition of Shikake: The Japanese Art of Shaping Behavior Through Design.

Though the word is native to Japanese, Dr. Naohiro Matsumura, author of Shikake: The Japanese Art of Shaping Behavior Through Design, has recontextualized it for the world of user experience design. His definition is as follows:

“Shikake are a means through which people become aware of those things they can see but do not see.”

In other words, shikake are environmental prompts that inspire the person to take action, on their own accord, without being explicitly told to do so.

Two examples of shikake from Dr. Matsumura’s book, Shikake: The Japanese Art of Shaping Behavior Through Design.

There are many examples of this:

A basketball hoop over a trashcan → Inspires people to throw away trash

A sticker of a fly in a urinal → Improves aim

Footprints on an escalator → Promotes orderly queuing and safe standing

Calorie indicators on steps → Incentivizes people to take the stairs for health

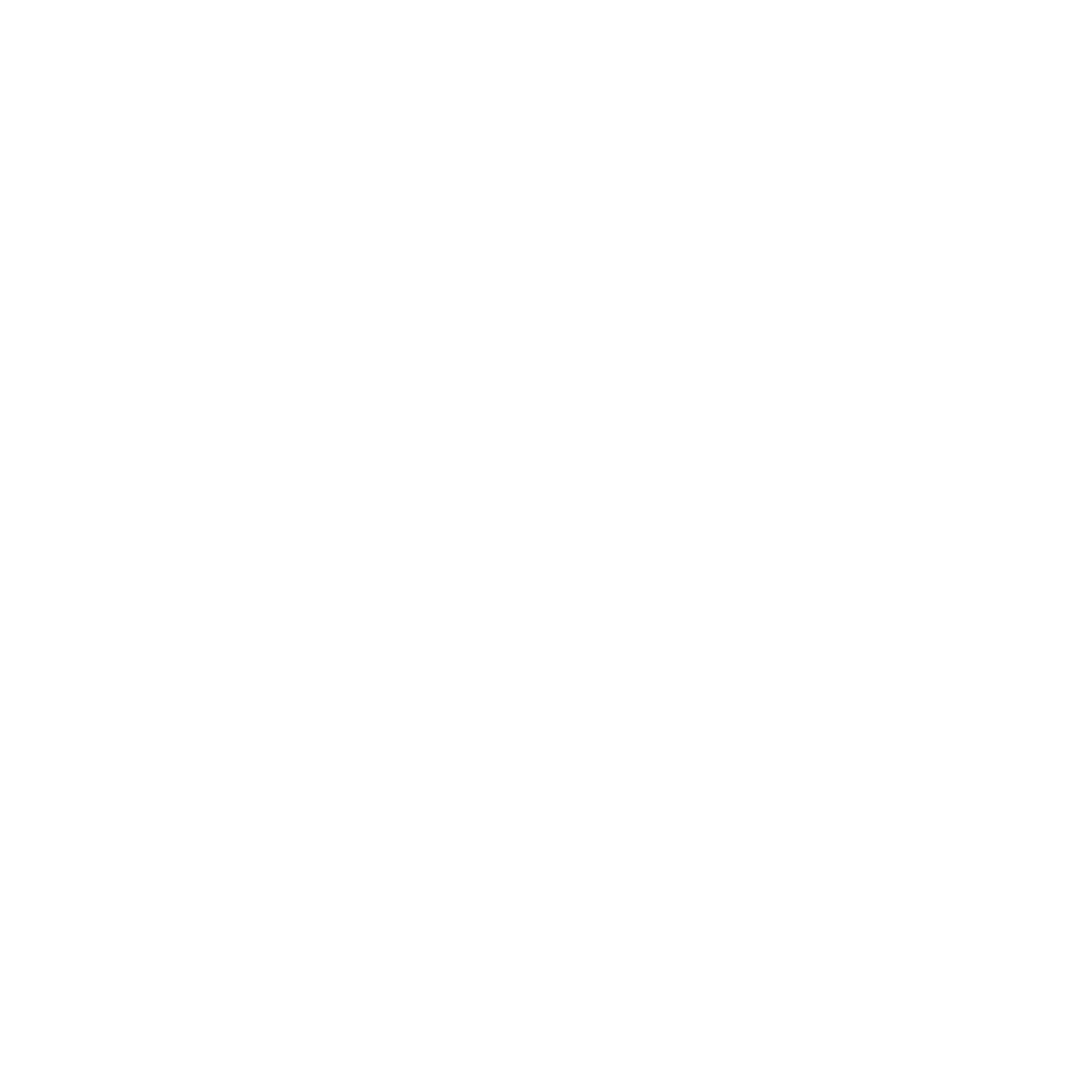

A single, composite image printed across the spine of a serialized manga series → Encourages readers to “collect them all”

Diagonal lines in a parking lot → Discourages double-parking and promotes alignment

Triangular toilet paper rolls → Reduces toilet paper waste by limiting how much is pulled

A coinbank that dispenses candy → Rewards saving.

There’s an even more aggressive form of shikake called poka-yoke, known as error prevention. It emerged as a salient feature of the Toyota Production System, developed by Shigeo Shinto, now the gold standard of automotive production.

These circles prevent bikes and other wheeled objects from occupying pedestrian-designated paths.

Together, these two systems work in tandem to allow us to design behavioral processes that assume human imperfection, instead appealing to our rational minds. The problem with reason, is that it assumes our most basic needs have been met. To someone struggling to make it through through their day-to-day, a tone-deaf appeal to recycle because it’s “good for the environment” can be registered as a personal assault. What we need is a new, more human language: one that’s not beseeching, but galvanizing.

–

At this point, readers of Nudge Theory by Thaler & Sunstein might be chomping at the bit to call foul: “This is just nudge theory repackaged.” But I’d argue the emphasis, the ethos, is entirely different.

In America, we tend to focus on making people choose to do what we want them to do. In Japan, the emphasis is on making people desire a socially beneficial outcome by making it delightful. This contrast is effectively illustrated through a comparison of Nudge and Shikake.

| Concept | Nudge (Thaler/Sunstein) | Shikake (Matsumura) |

|---|---|---|

| Framing | Behavioral Economics: Shapes Policy | Emotional Design: Shapes Environment |

| Action | "Choice Architecture” | “Behavioral Cueing” |

| Philosophical Root | Paternalism | Playfulness |

| User Autonomy | Steered | Activated |

| Medium | Abstract Space (Information, Decisions, Displays) |

Physical Space (Objects, Surfaces, Interfaces) |

| Goal | Foster better decisions | Encourage better behavior |

| Tone | Rational, utility-focused | Playful, socially-attuned |

| Methods | Defaults, framing, & presentation | Triggers, setups, & prompts |

| Focus | Ease, efficiency | Delight, participation |

| Examples | Default retirement plans, organ donor opt-outs | Trashcan hoops, manga spines, toilet rolls |

| Cultural Lens | Individualist, disembodied (cognitive thinking) |

Collectivist, embodied (bodily senses) |

See the difference?

It’s subtle, but I think it provides a partial explanation for the collective rebellion we’re witnessing in the US. People are tired of being studied, of being treated like mice, who can be goaded into an outcome desired by someone they don’t know. Silicon Valley, our established institutions, and even our government are all unwittingly contributing to this narrative: that people can’t be trusted to make their own decisions.

What we’re witnessing is something similar to a passenger taking control of the wheel and driving off the cliff, just to prove their own agency.

It’s time we recognize that people are doing their best and that institutions have failed them. It’s time for those of us lucky enough to be behind the wheel to design systems that meet people where they are.

—

This is where Shikake proves to be a particularly useful concept, because it feels closer to a kind of folk wisdom. It’s not just about efficiency, but affect. It understands that people don’t want to be “optimized”; they want to be surprised, delighted, and invited. They want to feel something—whether it’s a sense of satisfaction, play, purpose, or belonging.

The beauty of Shikake lies in its humility. Rather than assuming that people will read the manual, follow the signs, or make rational decisions, it meets them where they are: in a state of perpetual motion and distraction.

Shikake activates our human propensity for discovery and play.

It doesn’t say, “You should recycle.” It says, “Wouldn’t it be fun to make a basket?”

In this sense, Shikake doesn’t just shape behavior, it restores dignity to it.

In Western user experience design, we often fall into the trap of believing that clarity alone will inspire action. “If only people knew…” But clarity without care is just a flowchart. And people do not want to be pushed through a door, they want to choose to walk through it on their own accord.

What Shikake teaches us is that good design doesn’t simply remove barriers, it inspires, it entices. It respects the body as much as the brain.

This is especially true in website design. Digital space is an environment to which we are not native. We are physical beings, honed to respond to physical cues. The best web designers (like the team at Griflan) know how to use our evolutionary psychology to create delightful experiences. We use our physical biases for color, for movement, and tactile feedback to make the strange liminal space of the digital more palatable, more understandable, more usable.

Perhaps the goal isn’t to win people over, but to make them smile before they realize they’ve changed direction.